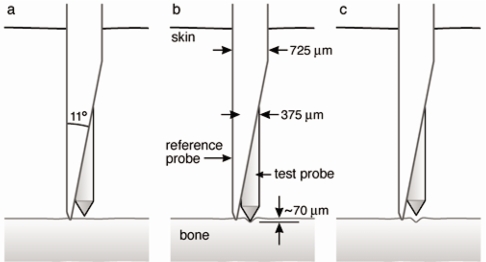

We would like to thank Allen and colleagues for their thorough review of reference point indentation (RPI) for assessing bone mechanical properties in vivo.(1) The authors have focused on two separate RPI devices, the BioDent® and the OsteoProbe®, and have gone to great lengths to compare and contrast these instruments, which differ considerably in their design, intended use, and output measures. In addition, the authors ask: what exactly are these devices measuring and how are these parameters related to traditional mechanical properties? While clearly these are important questions worthy of academic pursuit, with regards to the OsteoProbe®, a handheld device that is designed for use in the clinic, we believe the authors have “missed the forest for the trees”: the main practical question with this device is whether its output – the “bone material strength index (BMSi)” – is clinically useful.

Fragility fractures pose enormous medical, social and economic threats to society. Thus, a goal of clinical research is to better identify patients at risk for fractures. Although pharmacologic prophylaxis in patients at risk for fractures is efficacious,(2,3) it has significant side effects,(2,4) and treating everyone is unaffordable;(5) thus, there is a critical need to better characterize subsets of patients who are at sufficiently high fracture risk for treatment, but not well identified by established fracture prediction tools (i.e., areal bone mineral density (aBMD) T-score or WHO Fracture Risk Algorithm [FRAX®] score(6)]). One potential approach to accomplish this goal is to quantify components of “bone quality”, and establish the extent to which fracture risk prediction can be improved, specifically in the diagnostic evaluation of patients in whom clinical management remains most ambiguous. This includes, for example, the growing population of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in which aBMD and FRAX® significantly underestimate fracture risk.(7)

Using the OsteoProbe®, we recently demonstrated that 30 patients with T2DM had significant reductions in BMSi as compared to 30 matched non-diabetic controls despite no significant differences in aBMD by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA).(8) In addition, we found that serum glycated hemoglobin levels were negatively correlated with BMSi in the T2DM patients. Our findings suggest that the BMSi represents an aspect of bone material properties (independent of aBMD) that is impaired in patients with T2DM, particularly in those with worse chronic glycemic control. Therefore, regardless of what exactly the BMSi is measuring and how it relates to traditional mechanical properties, these findings suggest that this index may have potential clinical utility in identifying patients with T2DM at risk for fragility fractures.

We acknowledge that our results are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution as our sample size was relatively small and the findings were cross-sectional; thus, they need to be confirmed in larger prospective studies. In addition, whether patients with T2DM who suffer fragility fractures have further reductions in BMSi as compared to T2DM patients with no fracture history is not known, although answers to this and other emerging questions will be important in establishing whether impaired BMSi contributes to the underlying basis for diabetic fragility fractures.

Despite the uncertainty as to what exactly the OsteoProbe® is measuring, there is evidence supporting that BMSi is a measure of bone material properties. Thus, Bridges et al.(9) tested three calibration blocks (PMMA, brass, and Noryl) with both the Osteoprobe and a Rockwell Hardness tester and found that the BMSi increased with increasing hardness. It is important to note, however, that BMSi may or may not be simply and easily related to traditional bone mechanical parameters (e.g., toughness, elastic modulus, etc.), but still may have considerable utility as a clinical measure assessing some component(s) of bone material properties in a practical and convenient manner in patients.

Beyond the setting of T2DM, as reviewed by Allen et al.,(1) additional clinical studies have reported that BMSi was altered in response to osteoporosis therapies,(10) and not only differed among ethnic groups(11)but also between patients with and without fragility fractures.(12) Nevertheless, as with any new technology, additional testing will be required. Indeed, to better understand these issues, carefully designed studies which evaluate BMSi in women and men simultaneously, using identical, standardized procedures are needed to evaluate fracture risk beyond that provided by aBMD and FRAX®. In addition, issues related to measurement standardization and appropriate handling of outlier measurements are important, and will require consensus among the OsteoProbe® user community as well as strict implementation and reporting moving forward. Notably, steps are already being taken to address these issues.

In summary, we agree with Allen et al.(1) that we do not know exactly how the Osteoprobe output (BMSi) relates to traditional bone mechanical properties. However, the available evidence is clear that BMSi is providing some measure of bone material properties in vivo, which appears to be an assessment of bone quality beyond what is currently available from aBMD by DXA; thus, in the end, it may be of academic interest as to which specific traditional bone mechanical property BMSi is or is not related to, but the immediate, more practical question pertaining to the OsteoProbe® is whether or not its direct in vivomeasure – the BMSi – is clinically useful. Carefully designed studies are needed to test this important question and definitely establish whether the OsteoProbe® has a future in clinical practice.